修辞三段论及其应用研究

VIP免费

Contents

Acknowledgments………………………………………………………………………..i

ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………...…………………ii

摘要…………………………………………………………………………………......iv

List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………………....v

Chapter One Introduction ................................................................................................. 1

Chapter Two Rhetoric in Brief ..........................................................................................4

§2.1 A Synoptic History of Rhetoric ..........................................................................4

§2.2 A Comparison between Classical Rhetoric and Contemporary Rhetoric .......... 6

§2.2.1 Classical Rhetoric: The Art of Persuasion ............................................... 6

§2.2.2 Contemporary Rhetoric: Identification .................................................. 11

§2.2.3 A Comparison between “Persuasion” and “Identification” ................... 14

§2.3 Argument: The Core of Rhetoric ......................................................................15

Chapter Three A Theoretical Investigation of the Enthymeme .......................................17

§3.1 Definition of the Enthymeme ...........................................................................17

§3.2 Concepts Related to the Enthymeme ............................................................... 19

§3.2.1 Syllogism ............................................................................................... 19

§3.2.2 Probability ..............................................................................................21

§3.2.3 Topos ......................................................................................................22

§3.3 Features of the Enthymeme ............................................................................. 24

§3.4 The Role of the Enthymeme in Rhetorical Persuasion .................................... 32

§3.5 The Operational Mechanism of the Enthymeme ............................................. 37

§3.5.1 Construction of the Enthymeme ............................................................ 37

§3.5.2 The Operational Model of the Enthymeme ............................................39

Chapter Four The Application of the Enthymeme .......................................................... 47

§4.1 Application of the Enthymeme in Discourse Analysis .................................... 47

§4.1.1 Discourse Analysis: A Brief Survey .......................................................47

§4.1.2 The Enthymeme in Discourse Analysis ................................................. 48

§4.2 Application of the Enthymeme to the Teaching of English Writing ................ 55

§4.2.1 Problems with the Teaching of English Writing .................................... 55

§4.2.2 The Teaching of Invention via the Enthymeme ..................................... 57

§4.2.3 The Teaching of Organization via the Enthymeme ................................60

§4.2.4 The Enthymeme-Based Model in the Teaching of English Writing ...... 62

§4.3 Application of the Enthymeme to the Teaching of English Reading ............... 64

§4.3.1 The Interactive Process of Reading ....................................................... 64

§4.3.2 Problems with the Teaching of English Reading ................................... 65

§4.3.3 The Role of the Enthymeme in English Reading ...................................66

§4.3.4 An Approach in the Teaching of English Reading ................................ 68

Chapter Five Conclusion .................................................................................................72

§5.1 A Brief Summary of the Study .........................................................................72

§5.2 Limitations and Further Research .................................................................... 73

Appendix .........................................................................................................................75

Bibliography ................................................................................................................... 77

在读期间公开发表的论文 .............................................................................................82

Chapter One Introduction

1

Chapter One Introduction

In America, when people hear the word “rhetoric,” they are likely to think about

politicians intending to tell lies and distort the truth with “empty words” or beautiful

language. This is somewhat a humiliation to the rhetoricians who defined the art of

rhetoric in ancient Athens and Rome. In ancient times, rhetoric was utilized to get rid of

disagreement about important political, religious, or social issues; the study of rhetoric

was the study of being a qualified citizen.

It is obvious that not everyone shares the same idea. There are always different

opinions about things since people have different experiences in their lives. As Kenneth

Burke put it, “We need never deny the presence of strife, enmity, faction as a

characteristic motive of rhetorical expression” (1962: 20). Though disagreement among

human beings is inevitable, sometimes agreement must be achieved in order to work

things out. So the ancient rhetoricians invented rhetoric so that they would have means

of judging whose opinion was most accurate, or valuable. The aim of ancient rhetoric

was to activate the power that exists in languages among all the people by teaching the

principles of rhetoric. People who know about rhetoric know how to persuade others to

accept their opinions. It is a better choice for most people that rhetoric instead of

violence can help to get rid of disagreement. And the thousands of years’ history of

rhetoric may be an evidence of its vitality.

In China, rhetoric was once aimed at persuading people during the Spring and

Autumn Period and the Warring States Period. Politicians and scholars like Confucius

tried to persuade the emperor to accept their political theories. They left behind a good

record of their wise arguments. But since the Han Dynasty, Chinese rhetoric began to

center on written text instead of oral language. From then on, rhetoric has been serving

the appreciation of literature; it came to be considered as “modification of words or

expressions.”

When they realized that the narrow view of Chinese rhetoric is usually much too

limited to the study of sentences and the units below sentence level, many modern

scholars began to introduce the system of Western rhetoric. To quote Gorgias, rhetoric

was “the ability to persuade with words”(Hu, 2002: 8). And according to Aristotle, the

enthymeme is “the very body and substance of persuasion” (Rhetoric I, 1).

Thus the mastery of the enthymeme becomes the core of mastering rhetoric.

Research into the Enthymeme and Its Application

2

However, it seems that the enthymeme has not got its due attention, just as Aristotle

once said:

...Now, the framers of the current treatises on rhetoric have constructed but a small

portion of that art. The modes of persuasion are the only true constituents of the art:

everything else is merely accessory. These writers, however, say nothing about

enthymemes, which are the substance of rhetorical persuasion, but deal mainly with

no-essentials (Rhetoric, 1954: 20).

In the eyes of many people, the enthymeme is merely connected with scientific and

logical styles since it is often mentioned as “rhetorical syllogism.” In fact, the

enthymeme is also found in styles other than the previous two. It can be used

everywhere in our daily life. For example, the sentence “Mary will fail her final exam

because she hasn’t studied” is an enthymeme. The enthymeme is used so often that

people seldom notice that they are using it.

The history of enthymeme can be traced back to ancient Greece where Isocrates

(436-338 B.C.E.), one of the influential rhetoricians of the time, gave the enthymeme a

central place in his conception of rhetorical skill. And it was Aristotle who gave the

enthymeme a rough description and set up its position in rhetoric.

Despite the much attention he paid to the enthymeme, Aristotle failed to give a

clear definition to this concept. The study of the enthymeme, as it turned out, was put

aside for a long time. When the enthymeme became a hot topic again with the arising of

classical rhetorical study, the inexplicit definition made the academicians debate for a

long time. As a result, there are many different definitions of enthymeme, most of

which misunderstand the essence of the enthymeme.

In modern times, the enthymeme is often connected with syllogism, and it is

considered as “imperfect syllogism” by many academicians. If you have a close look at

the Rhetoric, you will find some differences in the definition and description between

the classical and modern rhetoric.

Under this circumstance, the first priority is to give a workable definition of the

enthymeme. Only when this is done, can the enthymeme be practically used.

Take the teaching of English writing to Chinese students as an example. It has long

been considered as one of the most difficult tasks in the English classroom. The students

are often bothered by questions like “what to say about it?” or “how to write?” And

Chapter One Introduction

3

teachers are challenged as well: How to help the students do better in the invention and

arrangement of their writing? How to improve their writing?

At this point, we may well take the enthymeme into account. The place of

enthymeme in the invention part of rhetoric, its persuasive effect and the importance of

the interaction between the speaker and the audience make it possible to be applied to

the teaching of writing and reading, especially the teaching of English writing.

In this thesis, Chapter One is a general introduction to the motivation of choice of

the rhetoric and the enthymeme as the subject of the thesis. Some current research on

the enthymeme is introduced, and objectives of the research are stated.

Chapter Two offers a brief review of the history of rhetoric and compares the

classical and the contemporary rhetoric in order to find out the essence of rhetoric.

Since the enthymeme is a kind of argument, the researches on argument are briefly

introduced in this chapter.

Chapter Three makes a detailed theoretical investigation into the enthymeme,

including its definition, features, role in the rhetoric and its operational model. All the

efforts are made to give a clear image of the enthymeme and provide convenience to

later applications of it.

Chapter Four applies the theory of the enthymeme to the fields of discourse

analysis, the teaching of English writing and the teaching of English reading in order to

show the practical value of the enthymeme.

Chapter Five is a conclusion of the thesis. Besides a brief summary, the author

states some limitations of the research in the thesis and points out the future efforts to be

made.

Research into the Enthymeme and Its Application

4

Chapter Two Rhetoric in Brief

§2.1 A Synoptic History of Rhetoric

In order to get the essence of rhetorical study, it is necessary to go over its two

thousand years’ history, which can be traced back to ancient Greece.

The study of rhetoric started in ancient Greece because people at that time began to

know the importance of giving speech. Then rhetoric became the course to train people

in how to persuade others. It became the study of the strategies of using words to

accomplish a purpose, that is, persuading people to do or to think what the speaker

wishes.

There are many famous rhetoricians who made great contributions to the

development of classical rhetoric. The three greatest ancient writers on rhetoric, who are

still frequently mentioned today, were Aristotle, Cicero and Quintilian. Aristotle was

considered as the greatest theoretician of rhetoric with his more philosophical principles

on rhetoric; Cicero was the greatest practitioner of rhetoric with a wonderful discussion

of theories applied to law cases, which can still work well today; and Quintilian was the

greatest teacher of rhetoric.

In Aristotle’s time, rhetoric was primarily concerned with oral language. This can

be proved by the original meaning of two words: Rhetor in Greek means orator, public

speaker, and rhetorike means public speaking. “To Aristotle’s world, teaching students

rhetoric meant teaching them to become orators. Deflection of rhetoric from oral

performance to written argumentation as such, vaguely incipient at best in Aristotle,

would occur only very slowly and imperceptibly over the centuries. Yet it must be

remembered that the oral speeches Aristotle was concerned with were in fact no longer

purely oral but were already being shaped by the chirographic milieu to post-oral

thought forms”(Horner, 1983: 3).

By the middle of the fourth century B.C. rhetoric had become the central discipline

in Greek education, affecting “all public utterances” and indeed all intellectual activity

(Kennedy, 1964: 7, 237, 268-72). The Romans made rhetoric more systematic. Due to

their efforts, rhetoric spread through the world in almost all fields of communication,

such as education and public activity, and in all forms of writing.

Classical rhetoric died with the collapse of the Roman Empire. However, the

Chapter Two Rhetoric in Brief

5

system established primarily by Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Quintilian survived, and

was modified by rhetors afterwards.

In the Middle Ages the classical tradition of rhetoric continued. However, rhetoric

at that time was not studied as a practical art. Instead, it became a kind of scholastic

exercise. The center of rhetoric became a study of the art of letter writing and of

preparing and delivering sermons. “Medieval rhetoric to a great extent then became a

series of adoptions of Ciceronian rhetoric to particular needs of the times, with

applications to problems of letter-writing, verse-writing, and preaching”(Horner, 1983:

49).

With the Renaissance, with the influence of Humanists, rhetoric became central

again. There came a revival of interest in the works of the classical rhetors. People made

use of Ciceronian rhetoric in discussions of philosophy, art, and religion. The study of

rhetoric during the English Renaissance made great progress. There were mainly three

groups: the Traditionalists—those who paid attention to the five parts that existed in the

classical rhetoric: invention, arrangement, style, memory, and delivery; the

Ramists—those who taught rhetoric included only style and delivery, and placed the

invention and arrangement to the field of logic; and the Figurists—those whose interest

centered on the study of the schemes and tropes. Though they had different pedagogical

methods, their fundamental conception of the art of rhetoric was actually the same.

These three groups contributed to the delivery of the classical rhetoric in England.

In the eighteenth century rhetoricians still followed the classical rhetoric. Most of

them regarded rhetoric as a practical art, much as Aristotle had conceived it. However,

by the end of the eighteenth century, classical rhetoric lost its dominant role, and

became nearly dead. According to Winifred Bryan Horner, “The eighteenth century

marks the end of a long tradition of rhetoric that had its beginning in Greece in the fifth

century B. C. and that for twenty centuries dominated philosophic thought and the

established institutions of church and government”(1983:101).

It was from the nineteenth century that the study of rhetoric changed a lot. The

term rhetoric was replaced by the term composition. Rhetoric’s association with oratory

was cut off, and composition now dealt exclusively with written text. The theoretical

method of writing in the rhetoric course was taken place by the approach of imitation

and practice. In the nineteenth century, therefore, political rhetoric was displaced by the

study of literature. Literature was made use of to teach freshman composition, and the

Research into the Enthymeme and Its Application

6

method paid much attention to style.

In the twentieth century, especially in the thirties and forties, various literary critics

made contribution to the revival of rhetoric. Among them are I. A. Richards and

Kenneth Burke. Meanwhile, people like Max Black and Lloyd Bitzer in the relatively

newly formed discipline of speech also associated their study with rhetoric. Philosophy

came to connect with rhetoric somewhat later, but in the fifties and sixties several

important philosophers have begun to call attention to rhetoric or call their own work

rhetorical, among whom there were Hannah Arendt in political theory, Stephen Toulmin

in logic, and Thomas Kuhn in philosophy of science. As a matter of fact, the

extraordinary expansion of colleges, especially in the sixties, necessarily involved an

expansion in first year writing programs. That expansion contributed to a growing sense

that the teaching of writing was best seen as rhetorical. Nowadays, it may well be said

that the study of rhetoric has been dispersed to many different fields of sciences.

The “new rhetoric,” developed during the last thirty years, is often considered as

the representative of contemporary rhetoric. The “new rhetoric” is the result of different

fields’ contributions. Whenever the “new rhetoric” is discussed, two figures are

unusually mentioned: I. A. Richards and Kenneth Burke. And Kenneth Burke with his

theory of “identification” has become the representative of contemporary rhetoric just as

Aristotle is considered as “father” of classical rhetoric.

It can be concluded from the history of rhetoric that classical rhetoric really had a

deep influence on the development of rhetoric. But still, after more than two thousand

years, what are the differences between the classical rhetoric and the “New Rhetoric”?

In the next part we will make a comparison between the representative theories of

Aristotle and Kenneth Burke.

§ 2.2 A Comparison between Classical Rhetoric and Contemporary

Rhetoric

§2.2.1 Classical Rhetoric: The Art of Persuasion

To Gorgias, rhetoric was “the ability to persuade with words”; to Isocrates, “The

artificer of persuasion”(Hu, 2002: 8); Aristotle has defined rhetoric as “the faculty of

Chapter Two Rhetoric in Brief

7

discovering in the particular case what are the available means of persuasion”(Cooper,

1932:7). It may be simply interpreted that rhetoric is the art of discovering and using the

most effective means of persuasion. It can be induced from the definitions that in the

classical sense, rhetoric is equivalent to persuasion. Persuasion is the center of classical

rhetoric. The term persuasion here is used in the broad sense to mean the influencing of

human behavior and attitude through the use of written and oral symbols.

According to Aristotle, there are three modes of persuasion: ethos,pathos and

logos. As it is said, a speech consists of three things: the speaker, the subject which is

treated in the speech, and the hearer to whom the speech is addressed (Rhetoric I,

3,1358a). It seems that this explains why only three modes of persuasion are possible.

These three appeals are the essence of the Aristotle theory. It should be made clear what

they are and how they work in the process of persuasion.

First, ethos “depends on the personal character of the speaker” (Rhetoric, 1954: 24).

It refers to the character of the speaker. Aristotle says, “We believe good men more fully

and more readily than others” (Rhetoric, 1954: 24). If the speaker appears to be credible,

the audience will form the second order judgment that propositions put forward by the

credible speaker are true or acceptable. He must display practical intelligence

(phronêsis), a virtuous character, and good will (Rhetoric II, 1, 1378a6ff). Without

showing the three elements in what he or she says, the effects of ethos cannot be

perceived. It is granted that if the quality of the person on the platform, on the television

screen, or behind the printed page is appreciated by the audience, there will be an

immediate effect of persuasion. But if the personality of the persuader is not acceptable,

it is hard to perceive persuasion among the audience. So it is taught that if you want to

be a competent salesman, the first thing you have to sell is yourself.

It is not easy to create a persuasive ethos because ethos always shows itself to

listeners or readers who inevitably build up an impression of the speaker or writer,

whether they agree with him or not.

Aristotle analyzed two kinds of ethical proof: invented ethos and situated ethos.

According to Aristotle, invented ethos is the character that can be invented suitable to an

occasion. If the rhetors enjoy a good reputation in the community, they can use it as a

situated ethos. The situated ethos can only be built up according to a long-term habitual

behavior. A person who has a bad reputation in the society may fail in achieving the

persuasive purpose in his speech or writing, no matter how beautiful his argument is.

摘要:

展开>>

收起<<

ContentsAcknowledgments………………………………………………………………………..iABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………...…………………ii摘要…………………………………………………………………………………......ivListofFigures……………………………………………………………………………………....vChapterOneIntroduction...........................................................................................

相关推荐

-

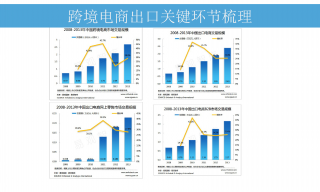

跨境电商商业计划书模版VIP免费

2025-01-09 29

2025-01-09 29 -

跨境电商方案范文VIP免费

2025-01-09 16

2025-01-09 16 -

创业计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 18

2025-01-09 18 -

xx生鲜APP计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 12

2025-01-09 12 -

跨境电商创业园商业计划书(盈利模式)VIP免费

2025-01-09 9

2025-01-09 9 -

跨境电商计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 14

2025-01-09 14 -

绿色食品电商平台项目计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 22

2025-01-09 22 -

农产品电子商务商业计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 9

2025-01-09 9 -

农村电商平台商业计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 14

2025-01-09 14 -

生鲜商城平台商业计划书VIP免费

2025-01-09 22

2025-01-09 22

作者:陈辉

分类:高等教育资料

价格:15积分

属性:83 页

大小:625.22KB

格式:PDF

时间:2024-11-20